- Home

- Krav Maga Blog

- Krav Instructors

- Train in Israel

- Tour Train Israel

- Krav Shop

- DVD

- Kickboxing

- IKI Near Me

- Seminars

- IKI Membership

- On-Line Training

- Krav Maga Training

- Testimonials

- History Krav Maga

- Instructors Page

- Past Blogs

- Spanish

- Italian

- Certification

- Contact

- Holland Seminar

- Vienna Seminar

- Poland Seminar

- Italy Seminar

- Belt Requirements

I remember palanka

BY Rabbi Isaac Klein

Written a long time ago...and now, December 21, 2021 as we approach midnight

Introduction by Moshe Katz, grandson

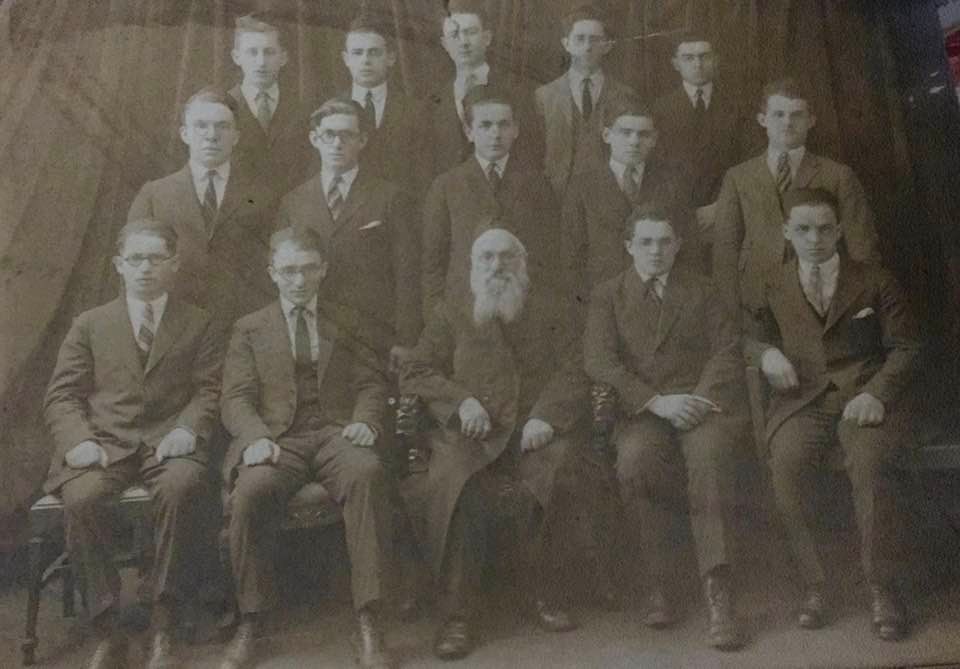

My grandfather in his Yeshiva days, (rabbinical academy), back row, center

My grandfather, the renown scholar and leader Rabbi Isaac Klein of blessed memory, passed away when I was only 17 years old. Most of that time our family lived far away from him, as such I only had limited contact with him. That contact, however brief, was profound.

His piety, humility, vast scholarship both religious and secular, his mild demeanor, left a deep impression on me.

I recall him visiting our home in New York, as he walked in the door and greeted each of the grandsons, he inquired; "What masechet/tractate of the Talmud are you currently studying?" with each reply he responded by quoting the opening section by heart. And then he would quietly say to each of us, "We will study together after dinner".

Through my mother I often heard stories about his life before emigrating to the United States of America. His older brother Uncle Bummie, (Abraham) did not make it, and like nearly our entire family, in fact our entire nation, were wiped out, murdered by the Nazis. My grandfather always felt grateful to the USA and in fact not only volunteered for service during World War Two, before there was a draft, but also called from the pulpit of his congregation for all American Jews to enlist and join the war effort. He landed in Europe on D Day at Utah beach and served as a military chaplain until the end of the war. After the war he served for two more years in Germany as military advisor for the Displaced Persons. My grandfather spoke 8 languages fluently and was immersed in European culture, as such he was well-suited for the job.

He was born in a village called Várpalánka, near Munkács Hungary, which is currently a place called Palanok, in Mukacheve, Ukraine.

My dear mother, his daughter, recently passed away, the last of her family. As such I have the difficult task of going through the entire house and making room for the new residents. Looking through an old volume of Talmud I found some old yellow paper with handwriting difficult to read. I began...I remember Palanka. I immediately realized this was written by my late grandfather. The stories were familiar to me, but I had never had it in his own words. I have decided to publish this for the benefit of others.

My grandfather was more than "honest", one might call him holy. It is said that the world rests on the virtue of 36 righteous men, and when one dies, another takes his place. My grandfather was regarded as one of the holy 36. In Hebrew the number 36 is Lamed Vav, (based on the letters of the Hebrew alphabet), he was referred to as a "Lamed Vavnik", one of the Thirty-Six Holy Ones.

I share this with you so that you have no doubt that every word written is the truth. Some of it may make some people uncomfortable, but know this; my grandfather never exaggerated, his way was one of gentleness, kindness, honestly, humility and compassion. I never recall him becoming angry. My dear mother inherited this virtuous quality. Sadly I did not.

He describes typical life for Jews in the Shtetel, the little village. Remember, what you are about to read is the truth.

Jewish life where my grandfather grew up, before the war.

On the eve of the Holocaust, Munkács (Mukačevo) was the largest and most important Jewish community in Subcarpathian Rus', Czechoslovakia. It was an Eastern European thriving community, known for its religious fervor, as well as substantial Zionist activities. In the final population census before the German invasion, conducted in January 1941, Munkács was noted to have 13,488 Jewish residents, some 42.7% of the total population of the town.

I Remember Palanka by Isaac Klein

Whoever heard of Plankah? It has nothing to do with the name Palanker, the noted family of Buffalo who hail from Romania.(Editor's note: at the time of this writing my grandfather lived in Buffalo, where he served as rabbi)

Palanka is the name of a little village (shtetl) near the better-known town of Munkatch (Munkacheva - when it became part of Czechoslovakia in 1918) (Note: Most Eastern European villages have many different spellings, depending on who ruled at the time).

To the Jews, the town was noted for its vibrant Jewish community, famous for its rabbinic dynasty as well as for the intensity of its Jewish inhabitants. In 1918 when most of the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe were plagued by Pogroms Munkatch and its environs were spared. (Editor's note: A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews.

Editor's note: The Slavic term originally entered the English language as a descriptive term for the 19 - 20th century attacks on Jews which occurred in the Russian Empire (mostly with the Pale of Settlement). Similar attacks against Jews which also occurred at other times and places retrospectively became known as pogrom).

The reason was simple. In the anarchic days of 1918 the Jews of Munkatch bore arms - and by permission of the famous Munkatcher Rebbe (Chief rabbi of Munkacs, a man who has followers to this very day) - even on Shabbos (Saturday, the Sabbath). The Pogromchicks were basically cowards and struck only where there was no resistance. In Munkatch there was resistance. When the contingent of the infamous Petlura gang came to Munkatch a reception committee was waiting for them at the railroad station. They returned to the train they came on but minus their arms. When rumors reached the city that in a nearby town their Jewish community was threatened a few ...armed Hassidim descended on the town, publicly punished the ring leaders, and there were no pogroms.

Palankah was on a main highway connecting the two cities Munkatch and Ungvar (Uzhhorod when it became Czechoslovakia in 1918. It had a few side streets but the Jews - with one exception lived on the main highway. I presume it was for reasons of safety. The non-Jewish population was not friendly. Jewish kids would not appear alone on the streets. They would invariably be beaten up by the Gentile kids. Their elders would rarely interfere. This was normal procedure. Since elementary education was compulsory, all the Jewish children attended elementary school. We went to school in groups or accompanied by adults. Otherwise we were sure to be beaten up. In America, even for Jews it is hard to conceive that Jewish children could not walk the street unaccompanied by adults. Even the nice law abiding citizens did not interfere when a Gentile kid or adult beat up a Jewish child. This resulted in our starting our day very early.

The first bell tolls at 7:30 am, the second at ten to eight, and classes started at eight. But Jewish children had to study their Judaism too. Hence, we went to school at six am. To put in some time in our Hebrew studies we would go to Hebrew school at six am. But that was the time when the Gentile boys brought the cows to the center of the village for the herdsman to take them out for pasture. Again it was not safe for us to appear on the street. Hence we started at 5 a.m.

This was the program of the average student. The diligent ones awaked an hour earlier. Hence their day started at 4 a.m. Thus we had a few hours of Hebrew studies under our belt before we went to public school. Lunch-hour was from 12 to 2 p.m. Our lunches were quite skimpy and the schools were near home. We did not need two hours for it. A greater part of the two hours were spent in "Heder" with our Hebrews studies.

Editors note: Heder literally means "room" in Hebrew and in Yiddish. The connotation is a place, a room, where young Jewish boys study Hebrew and Biblical texts. Heder is the earliest education for the young student, later on he moves up to Yeshiva, or "sitting" where he will study the Talmud). After four o'clock we again went back to our Hebrew studies and stayed there for hours. Sometimes the length depended on how long our candles would burn, for we studied at candle light and by kerosene lamps. With all that we were good students in both the Hebrew and the secular studies.

Vacation meant that instead of devoting only part of the day to our Hebrew studies we studied there the entire day. Vacation was the period during the holidays such as Passover and Succot. The American summer vacation did not exist for us. It simply meant that we devoted the entire day, starting at 4 a.m. to Jewish studies.

Did this regimen effect our health? Of course it did - but not as much as the professional detractors of the Heder would want us to believe. Our poor health was due much more to poor living condition and levels of adequate food. In the winter we suffered from the cold without proper clothing. The overall aspect to be noted is the intellectual emphasis and the growth of the mind. The principle Mens sana in corpore sano was not watertight. (Editor: Mens sana in corpore sano is a Latin phrase, usually translate as "a healthy mind in a healthy body". The phrase is widely used in sporting and educational contexts to express the theory that physical exercise is an important or essential part of mental and psychological well-being.) Those of us who point most attention to the mind did indeed become intellectuals rather than those who spent time in sports to develop the corpore sano.

But the greatest contributing factor was that we lived in a milieu where intellectual achievement elicited the highest praise. No report cards were necessary. If a student was a high achiever the whole community knew about it very soon and was not reticent in betraying this knowledge the the part concerned as well as to the community. Since studying was carried over to the adult life there was no death of knowledgeable laymen who would be eager to discuss with students the subject matter of their studies. Professor Heschel called this the Golden age of Jewish history when Jewish studies touched the greatest number of laymen, i.e. non-professional students.

The ordinary reader when discussing this phenomena usually conjures up a picture of the intensive life in Jewish communities like Vilna and Warsaw. Rarely does he figure that it was also towns of rural communities with a few dozen Jewish inhabitants. The fact is that the light of Jewish learning was burning bright.

Professor Finkelstein told us about his father. One night he could not fall asleep. During the day he came across a difficult passage in the Talmud. He thought he would wait until the next morning and then try again. But he could not fall asleep. At two in the morning he went back to the Beit Hamidrash (House of Study) to take another look at the passage. When he came there and took the tome of the Talmud from the shelf he could not find a place to put it down. Every bit of space was occupied by people deep in study.

But this was not uncommon. Ordinary people stayed up late for study. And so it was in my village of Palankah. This little village boasted of lay people who were scholars having studied for a number of years in famous yeshivas. (Editor: Rabbinical academies of higher learning). They became businessmen and artisans, but kept the habit of devoting some definite time for study. Indeed it was a case of "And all thy sons are well studied in God", which left out no one. And remember this village did not have a rabbi and yet learning was carried on by the more learned people investing their less learned brethren.

Ludwig Lewisohn in his book The Island Within tells this story: One evening in Warsaw he passed by a place where droshkies (cabs) were parked for blocks. In one of the halls he saw a gentleman leading a study group in discussion. He presumed that it was a conference of scholars for they participated in heated discussions. He assumed it was a meeting of scholars. When told that these were cab drivers and ordinary laborers he said in amazement, "What would be the corresponding phenomenon in an American community, if at five p.m. when a whistle blows in a factory, the laborers would hurry to libraries and study Plato or Aristotle in the original Greek. Fantastic - but a fact in the Jewish community of Eastern Europe.

So when I remember Palanka I think of this rich intellectual life that has vanished. Will our children have any idea of such a life!

Postscript by Moshe Katz

Long before I found this article, in my grandfather's own handwriting, I knew all these stories, for my dear mother, may she rest in peace, told me these.

My mother, may she rest in peace, loved telling these stories, and she was so proud of her father. I have carried these stories with me. When our Krav Maga students come to Israel, we visit the Holocaust museum and memorial Yad va Shem. As we pass on the bridge to the main museum, the bridge called, "The Bridge to a Vanished World", I tell this story about the cab drivers, the Jewish cab driver of Eastern Europe. I tell this story and then I say...it is all gone, Palanka and all these shtetlach, these little villages, the Jews are all gone. Most ended up going up in smoke in Auschwitz, or they were lined up and executed in the ravines and forest of Europe. The Jews of Europe are for the most part, no more.

This rich intellectual world that my grandfather describes, very much upset the Nazis, and it is...no more! It is vanished. The world is a poorer place without them.

My grandfather came to America, he survived. We carry on his tradition. I will tell his stories as long as I can.

and here is one more story...you see I come from a family of story tellers...

The last time I saw my grandfather was in Florida for my youngest brother's bar-mitzvah. My grandfather was weak. I recall visiting him in his hotel, there was a stack of Jewish books next to his bed, old Talmudic commentaries. He was never far from a book.

His last talk ...he quoted a Talmudic passage where the rabbis are asked, when is the best time to leave for a long journey, and the answer ...there is a particular time of day when your shadow produces another shadow. Today I see my shadow's shadow, I see my grandchildren studying the Talmud, I am ready for a long journey....

And I am still studying!

Additional footnote: January 5, 2026. Going through some old papers I found a snippet of an article written about my grandfather at the time of his retirement from the rabbinate, apparently he was close to 70 at the time. I believe he passed at the age of 73. My mother had saved this article all these years and I salvaged it from one of her drawers after her passing a little over 4 years ago. Sadly, I only found the second part of the article which began with.."Scholar Still at Work", continued from page 49. But there were some interesting historical tidbits which I believe add some more light to this story of his about his birthplace, Palanka. I must say that after all these years to hear my dear grandfather's voice again, speaking to us through this old faded newspaper clip, telling us, firsthand, a little about his childhood and his life, was most satisfying. A very pleasant surprise. I can hear his gentle voice and see his peaceful smile. I quote from the paper.

"Rabbi Klein is often asked how he manages to read and write so extensively and do so many other things.

His reply: "I get up early."

"There's a knack to not wasting time," he said. "I'm at my desk every morning between 5 and 6. I've been getting up every morning at 5 o'clock since I was 6 years old. I was born in 1905 on a farm in Hungary and we always got up very early. When I left for America in 1920 my part of Hungary had become part of Czechoslovakia. Today it is part of Russia. "

"By the time I left for America when I was 15, I was studying (Talmud, Torah, Jewish texts) 18 hours a day," he recalled. "I lived in a village where we had no electricity and we used candles and kerosene and many times how long I could study depended on how much kerosene we had or candlelight."

"I never had to be coaxed to study, " he went on, "I always had a great desire to read. I read everything I could get my hands on. (Moshe: When he passed he a library containing over 10,000 volumes, and he was never a rich man. He also wrote at least 10 books, and translated some ancient Hebrew books to English.) I never ate alone without having a book in my hands."

Rabbi Klein never goes anywhere without a book in his pocket. "Even if it's only 10 minutes, I'll take it out and read if I'm early for an appointment or waiting to meet someone. That's what I mean about the knack of not wasting time."

My grandfather Chaplain Isaac Klein, World War Two.